Advanced Patterns — What the Best dApps Do

The capstone. After six articles building foundations, we now dissect the architectural DNA of GRIDNET OS’s most sophisticated dApps — the Wallet at 37,000+ lines, the Messenger with its real-time swarm mesh, and the patterns that separate competent dApps from exceptional ones. Every claim here is verified against actual source code.

1. Introduction — Why Advanced Patterns Matter

There is a moment in every developer’s journey — somewhere between the first prototype and the thousandth user — when the code that once seemed elegant begins to buckle. State becomes inconsistent. Network calls race against each other. Security assumptions that held in development collapse in production. The patterns explored in this article are the antidotes to those collapses.

The GRIDNET OS Wallet dApp (wallet.js) is perhaps the most instructive case study on this platform: at over 37,000 lines, it manages cryptographic key chains, constructs and signs transactions locally, tracks nonces across blockchain forks, encrypts sensitive data with PIN-derived keys, polls for on-chain confirmation, and renders a fully responsive cyberpunk UI — all inside a single Shadow DOM–isolated CWindow instance. It is, by any measure, a production-grade decentralized application running entirely in the browser.

This article distils the patterns that make it work. These are not theoretical — they are extracted directly from the source code of shipping dApps.

2. Multi-Thread Architecture

GRIDNET OS dApps do not run as single-threaded event handlers. They operate within a process-and-thread model that mirrors an operating system’s concurrency primitives, implemented entirely in JavaScript.

The CVMContext Singleton

At the heart of every dApp sits CVMContext — a singleton instantiated once and shared across the entire OS session. Its constructor (found in VMContext.js) reveals the scope of its responsibilities:

// From VMContext.js constructor

this.mRecentRequestID = 0;

this.mJSThreads = [];

this.mPendingRequests = new Map(); // Maps request IDs to {resolve, reject, type, timer}

this.mProcesses = [];

this.mUserModeProcessIndex = 1000; // below are kernel-mode processes

this.mControllerThreadInterval = 2000;

Each dApp receives a unique process ID via getNewProcessID(), and within that process can spawn multiple JS Threads — lightweight interval-based execution loops managed by CJSThread objects. The critical method is createJSThread():

// From VMContext.js

createJSThread(funcPtr, processID, intervalMS, autoRun, isKernelMode) {

if (this.creatingThreadMutex) {

CTools.getInstance().logEvent('already creating a thread.');

return 0;

}

try {

this.creatingThreadMutex = true;

let threadObj = new CJSThread(funcPtr, processID, intervalMS);

this.mJSThreads.push(threadObj);

if (autoRun) threadObj.start();

return threadObj.id;

} finally {

this.creatingThreadMutex = false;

}

}

Note the mutex guard (creatingThreadMutex) — even in single-threaded JavaScript, re-entrant calls during async operations can corrupt shared state. This pattern appears throughout the codebase.

The Wallet’s Concurrent Threads

The Wallet dApp orchestrates at least four concurrent concerns:

- Controller Thread — a periodic loop (configurable via

mControllerThreadInterval, default 20 seconds) that refreshes balance, transaction history, and token pool metrics. - Auto-Lock Timer — checks every 10 seconds whether the inactivity threshold has been exceeded (

startAutoLockTimer()). The comment in source explicitly notes: “Performance optimization: Check every 10 seconds instead of 5 to reduce CPU usage.” - Transaction Monitor —

awaitTransactionResult()pollsgetTransactionDetailsA()every 10 seconds indefinitely until a result is received or the user aborts. - Token Pool Generation — runs hash chain generation in a background thread with progress callbacks, deliberately designed to “not freeze the UI.”

Request ID Tracking

Every asynchronous request flowing through CVMContext receives a monotonically increasing ID via genRequestID(). The mPendingRequests Map tracks each outstanding request with its resolve/reject callbacks and a timeout timer. This is the backbone of the platform’s promise-based async API — methods like getDomainDetailsA() and getTransactionDetailsA() register a request, send a network message, and return a Promise that resolves when the matching response arrives.

// Pattern: Request-response correlation

genRequestID() {

return (++this.mRecentRequestID);

}

// mPendingRequests.set(requestID, { resolve, reject, type, timer });

3. State Management at Scale

The Wallet manages state across three distinct tiers, each with different lifetimes and persistence mechanisms.

Tier 1: Ephemeral UI State

This is the state that lives and dies with the dApp instance: which tab is active (mViewState.activeTab), DOM element references cached in the mElements object, the current PIN in memory (mCurrentPIN), pagination state, and transient tracking structures like mPendingTransactionsMap and mMempoolNonces.

The Wallet takes care to clear sensitive ephemeral state when locking:

// From lockWallet()

async lockWallet() {

if (this.mRecipientsLoaded && this.mCurrentPIN) {

await this.encryptAndStoreRecipients(this.mCurrentPIN, true);

}

this.mIsLocked = true;

this.mCurrentPIN = ''; // Clear PIN from memory

this.clearPINDisplay();

}

Tier 2: Persistent Settings

The CSettingsManager and CAppSettings classes provide a key-value persistence layer, identified by package ID (org.gridnetproject.UIdApps.wallet). The Wallet’s saveSettings() method serializes dozens of fields — from walletPIN (the PBKDF2 hash, never the plaintext) to transactionVersion, refreshInterval, and encryptedRecipients.

The settings system uses a static accessor pattern required by the framework:

// Required by CSettingsManager

static getSettings() {

return CUIWallet.sCurrentSettings;

}

static setSettings(sets) {

if (!CTools.getInstance().isInstanceOf(sets, 'CAppSettings'))

return false;

CUIWallet.sCurrentSettings = sets;

return true;

}

Tier 3: Blockchain-Derived State

The richest and most complex tier. CDomainDesc objects carry account balance and nonce. CTransactionDesc objects carry full transaction details with status, height, validation results, and GridScript execution logs. CSearchResults provides paginated access to query results. All are retrieved asynchronously via CVMContext’s blockchain explorer API and cached with timestamps (mCachedHeight, mCachedHeightTimestamp).

The interplay between these tiers is where complexity lives. The forecasted nonce, for instance, is derived from the blockchain-reported actual nonce (Tier 3), modified by pending mempool transactions (Tier 1), and persisted indirectly through the pending transactions timeout configuration (Tier 2).

4. Transaction Pipelines

The Wallet supports two distinct transaction modes: Decentralized Processing Thread (DPT), where GridScript commands are sent to a remote full-node thread, and Local Transaction Mode, where transactions are compiled, signed, and submitted entirely client-side. The local mode is the more architecturally interesting — it eliminates trust in the processing node.

Stage 1: GridScript Compilation

The GridScriptCompiler (in GridScriptCompiler.js) compiles human-readable GridScript source into V2 bytecode. The V2 format prepends a version byte and a 32-byte SHA-256 hash chain for keyword image verification — directly compatible with the C++ GRIDNET Core implementation:

// From GridScriptCompiler.js // V2 (current): [VERSION_BYTE][32_BYTE_HASH][OPCODES...] // OPCODE ENCODING: // - ID <= 127: Single byte [ID] // - ID > 127: Two bytes [HIGH_BYTE | 0x80][LOW_BYTE] this.BYTECODE_ID_UNSIGNED = 1; this.BYTECODE_ID_SIGNED = 2; this.BYTECODE_ID_DOUBLE = 3; this.BYTECODE_ID_USER_OPCODE = 4; this.BYTECODE_ID_STRING_LITERAL = 5; this.GRIDSCRIPT_IMAGE_INIT_STRING = "GRIDSCRIPT_V2_KEYWORD_IMAGE";

The compiler runs entirely in the browser using the Web Crypto API for SHA-256 hashing, with a Node.js fallback for server-side usage — a pattern of environment-agnostic design that appears throughout the crypto utilities.

Stage 2: Transaction Construction

The CTransaction class assembles a complete transaction from the compiled bytecode, the issuer’s domain ID, public key, nonce, timestamp, ERG (energy resource gas) bid and limit, and optional extension data:

const tx = new CTransaction(

issuer, // domain ID

pubKey, // public key

txNonce, // nonce (forecasted)

bytecode, // compiled GridScript

timestamp, // Unix timestamp

ergBidAttoGNC, // ERG price (BigInt)

ergLimit, // ERG limit (BigInt)

new Uint8Array(), // extData

0, // lockTime

txVersion // 2 or 3

);

Stage 3: Client-Side Signing

The transaction is signed with the user’s private key, retrieved from the CKeyChainManager after authentication. This is the security-critical moment — the private key exists in memory only transiently, and the Wallet takes pains to clear it:

const signSuccess = tx.sign(privKey);

if (!signSuccess) {

throw new Error('Failed to sign transaction');

}

Stage 4: BER-Encoded Submission

The signed transaction is packed into BER (Basic Encoding Rules) format and submitted via submitPreCompiledTransactionA(). The response contains a receipt ID — a base58check-encoded identifier used for all subsequent tracking:

const packedTx = tx.getPackedData(false);

const submitResult = await this.mVMContext.submitPreCompiledTransactionA(

packedTx, this, this.getThreadID, 30000

);

const receiptID = this.mTools.encodeBase58Check(submitResult[0]);

Stage 5: On-Chain Monitoring

After submission, awaitTransactionResult() enters an indefinite polling loop — querying getTransactionDetailsA() every 10 seconds. The monitoring handles five distinct result states: success (result 0), processing (results 100-199), forked out (continuing to wait for re-confirmation), invalid nonce (race condition detected), and error (terminal failure). Users can close the monitoring view without losing their transaction.

Nonce Forecasting

Perhaps the most sophisticated subsystem. The Wallet maintains both an mActualNonce (from the blockchain) and an mForecastedNonce (actual + pending mempool transactions). Gap detection scans mempool nonces for discontinuities, with a 30-second grace period before alerting. Terminally invalid transactions (nonce ≤ actual) are explicitly filtered out to prevent poisoning the forecast:

// CRITICAL FIX: Skip transactions with nonce <= mActualNonce

if (this.mActualNonce !== null && txNonce !== undefined) {

if (txNonce <= this.mActualNonce) {

console.warn(`Ignoring terminally invalid mempool TX: nonce ${txNonce} <= account nonce ${this.mActualNonce}`);

continue;

}

}

5. Real-Time Collaboration — WebRTC Swarm Patterns

GRIDNET OS's real-time collaboration infrastructure — used by the Messenger and Meeting dApps — is built on a WebRTC swarm mesh managed by two key classes: CSwarmsManager (singleton, resource optimizer) and CSwarm (individual swarm instance).

The Swarm Lifecycle

Each CSwarm instance (defined in swarm.js) manages its own set of peer connections, ICE candidates, and SDP offer/answer exchanges. The constructor reveals the architectural breadth:

// From CSwarm constructor

this.mRTCCfg = {};

this.mRTCCfg.iceServers = this.mVMContext.ICEServers;

this.mPeerReachableTimeoutMS = 5000;

this.mConnQualityMaxThreshold = 1000; // MS

this.mConnQualityHighThreshold = 1500;

this.mConnQualityMediumThreshold = 2000;

this.mConnQualityLowThreshold = 3500;

this.mControllerThreadInterval = 100; // 100ms controller loop

this.mPeersPingIntervalMS = 250;

this.mSwarmAuthReq = eSwarmAuthRequirement.open;

this.mKillWhenNoProcesses = true;

this.mClientProcesses = [];

Connection quality is measured through ping latency thresholds (1000ms max, 3500ms low), and the swarm controller runs at a tight 100ms interval — ten times faster than typical application threads — reflecting the latency-sensitive nature of real-time communication.

Virtual Device Abstraction

One of the most ingenious patterns in the codebase is the virtual device layer. CVirtualCamDev creates a black-screen video track from a canvas element, and CVirtualAudioDev creates a silent audio track from a Web Audio oscillator:

// CVirtualCamDev - generates a dummy video track from canvas

constructor(widthP = 640, heightP = 480) {

let canvas = Object.assign(document.createElement("canvas"), { width, height });

canvas.getContext('2d').fillRect(0, 0, width, height);

let stream = canvas.captureStream(25);

this.mTrack = stream.getVideoTracks()[0];

}

// CVirtualAudioDev - generates a silent audio track from oscillator

this.mOscillator = this.mAudioCtx.createOscillator();

this.mOscillator.type = 'sine';

this.mOscillator.frequency.setValueAtTime(440.0, this.mAudioCtx.currentTime);

These virtual devices serve a critical purpose: WebRTC peer connections can be established before the user grants camera/microphone access. The dummy tracks maintain the connection structure, and real hardware tracks are hot-swapped in when available — a pattern the source calls "Dummy → Real tracks."

Resource Optimization

CSwarmsManager.optimizeRequestedResources() continuously reconciles hardware resource allocation across all active swarms. If no swarm requires the camera, the camera track is stopped (releasing the hardware and turning off the LED indicator). The code explicitly comments on the privacy implications: releasing unused hardware is "of paramount importance to the user's overall privacy-related wellbeing."

Capability Negotiation

Each swarm connection operates with three distinct capability layers:

mAllowedCapabilities— maximum capabilities the swarm supports (default: audioVideo)mEffectiveOutgressCapabilities— what is actually being sent (default: data only)mEffectiveIngressCapabilities— what is accepted from peers (default: audioVideo)

This separation allows fine-grained control: a user can join a meeting swarm with data-only capability, then upgrade to audio, then video — without renegotiating the connection.

6. Security Hardening

The Wallet implements defense in depth — multiple overlapping security layers, each designed to function independently.

PIN Protection with PBKDF2

The PIN is never stored. Instead, a random salt is generated, and the PIN is hashed using PBKDF2 with 100,000 iterations of SHA-256. The resulting hash and salt are stored; verification re-derives the hash and compares using constant-time comparison to prevent timing attacks:

// Constant-time comparison to prevent timing attacks

let match = true;

for (let i = 0; i < enteredHash.length; i++) {

if (enteredHash.charCodeAt(i) !== storedHashBase64.charCodeAt(i)) {

match = false;

// Note: does NOT return early — continues loop

}

}

return match;

The source comments are explicit: "Both strings should be same length if hashing worked correctly" — the length check occurs before the loop, and the loop always runs to completion regardless of mismatches.

AES-256-GCM Recipient Encryption

Saved recipients are encrypted with AES-256-GCM using a key derived from the PIN via PBKDF2. Each encryption operation uses a fresh 12-byte random IV. The encryptAndStoreRecipients() method includes a critical detail: when the PIN is set but not provided (e.g., session expired), it refuses to save rather than saving in plaintext:

if (this.isPinSet) {

if (!pin) {

console.error('[Recipients] PIN is required but not provided');

return false; // Refuse to save without encryption

}

}

Corrupted Data Recovery

One of the more remarkable patterns is the transparent data recovery in decryptAndLoadRecipients(). If decryption fails, the code attempts to parse the encrypted field as raw JSON. If it succeeds (indicating a corrupted save where data was stored unencrypted), it automatically re-encrypts with the current PIN:

try {

recipientsJSON = await this.decryptWithPIN(this.mEncryptedRecipients, pin, this.mWalletPINSalt);

} catch (decryptError) {

try {

const parsed = JSON.parse(this.mEncryptedRecipients);

if (Array.isArray(parsed)) {

this.mRecipients = parsed;

this.mRecipientsLoaded = true;

await this.encryptAndStoreRecipients(pin); // Auto-repair

return true;

}

} catch (jsonError) {

throw decryptError; // Re-throw original

}

}

Client-Side Pre-Validation

Before submitting transactions to the network, the Wallet performs client-side pre-validation that mirrors GRIDNET Core's preValidateTransaction() heuristics. Using the cached CDomainDesc, it predicts whether a transaction will succeed or fail — providing immediate feedback without waiting for network round-trips:

if (!incoming && this.mCurrentDomainDesc) {

txDesc.preValidate(this.mCurrentDomainDesc);

expectedResult = txDesc.getLastPreValidationResult();

expectedResultText = txDesc.getExpectedResultText();

expectedResultColor = txDesc.getExpectedResultColor();

}

Session Security

At the CVMContext level, the platform supports AEAD (Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data) for authentication, outgress message signing, peer public key verification, and session key exchange — configurable per connection:

// From CVMContext constructor this.mUseAEADForAuth = false; this.mUseAEADForSessionKey = false; this.mSignOutgressMsgs = false; this.mAuthenticateHello = true; this.mAuthenticationRequired = false; this.mEncryptionRequired = true;

7. Performance Optimization

The Wallet's source code is annotated with dozens of performance-related comments, each documenting a specific optimization and its rationale. These are not afterthoughts — they represent hard-won lessons from production usage.

Debouncing and Rate Limiting

Balance retrieval is debounced with a minimum interval. Error notifications are rate-limited to once per 30 seconds. The auto-lock timer checks every 10 seconds rather than 5. Each of these decisions is documented inline:

// Performance optimization: Debounce balance retrieval

const timeSinceLastRetrieval = now - this.mLastBalanceRetrievalTime;

if (!immediate && timeSinceLastRetrieval < this.mBalanceRetrievalMinInterval) {

if (this.mBalanceRetrievalDebounceTimer) {

clearTimeout(this.mBalanceRetrievalDebounceTimer);

}

const delay = this.mBalanceRetrievalMinInterval - timeSinceLastRetrieval;

this.mBalanceRetrievalDebounceTimer = setTimeout(() => {

this._retrieveBalanceInternal();

}, delay);

return;

}

BER Decoding Offloading

The CVMContext constructor initializes a BERDecoderProxy — a Web Worker that offloads ASN.1/BER decoding to a background thread. The source notes that BER decoding creates "~95 nested function calls per transaction," making it a major CPU bottleneck. The mempool fetch size was reduced from 100 to 25 specifically because "BER decoding is expensive."

Thumbnail Generation Pausing

During heavy operations like transaction history loading, the Wallet pauses CWindow's thumbnail generation:

// Performance optimization: Pause window thumbnail generation

// dom-to-image.js consumes 77% of CPU time during heavy operations

if (typeof CWindow !== 'undefined' && CWindow.pauseThumbnailGeneration) {

CWindow.pauseThumbnailGeneration();

}

The comment reveals a remarkable profiling insight: the taskbar thumbnail renderer (dom-to-image.js) was consuming 77% of CPU time during data-heavy operations. Pausing it during bulk loads and resuming afterward — even on error paths — is a pattern that any complex CWindow dApp should adopt.

Parallel API Calls

Transaction history loading uses Promise.all() to fetch mempool and on-chain data simultaneously:

const [mempoolResults, onChainResults] = await Promise.all([

this.mVMContext.getRecentTransactionsA(25, 1, true, new ArrayBuffer(0), this),

this.mVMContext.getDomainHistoryA(this.mCurrentDomain, pageSize, page, ...)

]);

The results are then merged client-side, with pending transactions sorted to the top. This pattern halves the perceived latency compared to sequential fetching.

Intelligent Table Updates

The Wallet uses Tabulator's replaceData() instead of destroying and recreating tables, preserving scroll position and reducing DOM churn. Non-critical redraws are deferred to requestIdleCallback:

if ('requestIdleCallback' in window) {

requestIdleCallback(() => {

if (this.mRecentTxTable) {

this.mRecentTxTable.redraw();

}

});

}

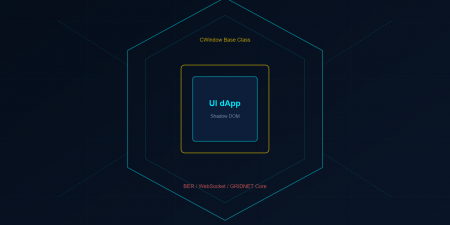

8. Multi-Instance Patterns — Shadow DOM Isolation

Every CWindow dApp renders inside a Shadow DOM boundary. This is not merely a styling convenience — it is an architectural necessity for a multi-window operating system.

The getControl() and shadowQuery() Pattern

The Wallet accesses its DOM exclusively through Shadow DOM–aware selectors. this.getControl('element-id') and this.shadowQuery('#selector') operate within the shadow root, ensuring that two Wallet instances (or a Wallet and a Terminal) cannot accidentally cross-reference each other's elements.

This isolation extends to CSS. The Wallet's 2,000+ lines of embedded styles — from the cyberpunk header gradients to the Tabulator theme overrides — are scoped to its shadow root. Container queries (@container settings (max-width: 800px)) respond to the CWindow's actual dimensions rather than the viewport, enabling truly responsive dApp layouts within arbitrary window sizes.

Event Listener Cleanup

The CSwarmsManager.unregisterEventListenersByAppID() method demonstrates the cleanup pattern essential for multi-instance environments. When a dApp window is closed, all its registered event listeners across swarms, connections, and the swarm manager itself must be purged:

unregisterEventListenersByAppID(appID, eventListener) {

// Clean swarm connections

for (let i = 0; i < this.mSwarms.length; i++) {

let connections = this.mSwarms[i].peers;

for (let y = 0; y < connections.length; y++) {

connections[y].unregisterEventListenersByAppID(appID, eventListener);

}

}

// Clean swarms themselves

for (let i = 0; i < this.mSwarms.length; i++) {

this.mSwarms[i].unregisterEventListenersByAppID(appID, eventListener);

}

// Clean manager-level callbacks

// ...

}

9. Error Recovery and Resilience

Production dApps fail. The question is not whether they fail, but how gracefully they recover.

The Rollback Pattern

Every mutation to the encrypted recipients list follows a strict rollback protocol. Before modifying the array, the old state is saved. If the subsequent encryption and save operation fails, the array is restored to its previous state:

async updateRecipient(id, address, nickname, notes) {

const index = this.mRecipients.findIndex(r => r.id === id);

const oldRecipient = { ...this.mRecipients[index] }; // Save for rollback

this.mRecipients[index].address = address;

// ... update fields ...

const success = await this.encryptAndStoreRecipients(this.mCurrentPIN);

if (!success) {

this.mRecipients[index] = oldRecipient; // Rollback

return false;

}

return true;

}

This pattern is applied identically to addSavedRecipient(), updateRecipient(), and deleteRecipient(). If the PIN has expired during the operation, the Wallet forces re-authentication rather than saving unencrypted data.

Blockchain Fork Recovery

The transaction monitor handles blockchain forks as a normal operational condition. When a transaction is "forked out" (its block was replaced by a competing chain), the monitor continues polling for re-confirmation rather than reporting an error. When an invalid nonce is detected — indicating a fork race condition between two sequential transactions — the Wallet diagnoses the root cause and prompts the user to retry:

} else if (txDetails.result === eTransactionValidationResult.invalidNonce) {

console.error('Registration TX has invalid nonce (likely fork race condition)');

this.showNotification(

'The identity registration transaction was rejected due to an invalid nonce.\n\n' +

'This is typically caused by a blockchain fork...',

'Fork Race Condition Detected', 'warning'

);

}

Transient vs. Permanent Error Discrimination

The balance retrieval error handler distinguishes between transient network failures and permanent "not found" errors. Only the latter resets nonce state — transient failures preserve the existing state to prevent disruption to pending transactions:

// CRITICAL: Only reset nonce state if domain doesn't exist

if (isNotFound) {

this.resetNonceState();

} else {

console.log('Transient error — preserving nonce state');

}

Resource Cleanup on Error Paths

Every try/catch block in the transaction history loader includes cleanup in the error path — resuming thumbnail generation, removing loading indicators, and restoring table state. The pattern "resume even on error" prevents resource leaks and UI freezes.

10. The Complete Architecture

Having examined each pattern individually, let us now assemble them into the reference architecture that production GRIDNET OS dApps embody.

The Three Layers

| Layer | Components | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| UI Layer | Shadow DOM, Tabulator, Modal System, Responsive (Container Queries), GLink deep links | Rendering, input handling, style isolation, cross-dApp navigation |

| Application Layer | State Machine (3-tier), TX Pipeline, Security (PIN/AES), Performance (debounce/cache), Token Pools, Keychain Management | Business logic, cryptography, transaction lifecycle, off-chain payments |

| Platform Layer | CVMContext, CWindow, GridScriptCompiler, Blockchain API, WebSocket, BER encoding, WebRTC Swarms | OS services, network transport, bytecode compilation, consensus |

The Ten Commandments of Production dApps

From the patterns we've examined, ten principles emerge:

- Never trust a single data source. Forecast nonces from multiple signals (actual nonce + mempool + pending map). Validate transactions client-side before network submission.

- Always save before mutating, and rollback on failure. The Wallet's recipient operations are the template.

- Distinguish transient from permanent errors. Network timeouts should not reset critical state. "Not found" errors should.

- Debounce everything that touches the network. Balance checks, error notifications, mempool fetches — all need rate limiting.

- Offload heavy computation. BER decoding goes to Web Workers. Token pool hash chain generation runs in background threads.

- Pause what you don't need. Thumbnail generation pauses during bulk loads. Oscillators disconnect when not streaming. Camera LEDs turn off when no swarm needs video.

- Handle the fork. Blockchain state can change retroactively. Any system tracking nonces or confirmations must handle forked-out transactions gracefully.

- Security is layered, not binary. PBKDF2 for storage, AES-GCM for encryption, constant-time comparison for verification, auto-lock for inactivity, and state clearing on lock — each layer works independently.

- Clean up after yourself. Unregister event listeners by app ID. Resume paused systems even on error paths. Clear sensitive data from memory when locking.

- Document your performance decisions. Every optimization in the Wallet source is annotated with its rationale. Future maintainers — including your future self — will thank you.

Final thought. The patterns described in this article did not emerge from theoretical design sessions. They emerged from users encountering forks, from developers profiling BER decoding bottlenecks, from security auditors questioning timing attack vectors. The best dApps are not written — they are forged, line by line, in the furnace of production use.

If you have followed this series from Article 1 through to this capstone, you now possess the complete vocabulary of GRIDNET OS dApp development: from spawning your first CWindow to orchestrating multi-threaded transaction pipelines with fork-resilient nonce forecasting. Build something extraordinary.

📚 UI dApp Developer Series

- Your First dApp — CWindow, Shadow DOM, and the GRIDNET OS Lifecycle

- Talking to the Blockchain — CVMContext, Threads, and the Message Bus

- State & Storage — Settings, Persistence, and Reactive UI

- Files, Streams & the Decentralized Web — DFS and Content Handling

- Real-Time dApps — WebRTC Swarms, Media, and P2P Communication

- Deploying & Distributing — Packaging, GLinks, and the App Ecosystem

- Advanced Patterns — What the Best dApps Do ← You are here