Introduction — The Deployment Journey

Every civilisation that ever mastered fire eventually learned to contain it. The raw, untamed energy of combustion became the controlled flame of a forge, then the precise heat of a kiln, and finally the regulated burn of an engine. Software follows an identical arc. The code you have been writing throughout this series — the HTML scaffolding, the GridScript logic, the event-driven dance between your dApp and the decentralised virtual machine — all of that has been fire in the wild. Powerful, yes. Potentially destructive if loosed onto a production blockchain without the ceramic vessel of a proper deployment pipeline.

This article is that vessel. We shall walk, line by line through the actual source code, from the moment your dApp exists as editable files in a local sandbox to the moment it becomes an immutable, cryptographically signed, consensus-validated entity on the GRIDNET OS Decentralised File System (DFS). Along the way you will encounter the GridScript compilation pipeline, the V2 bytecode format with its keyword hash chain verification, the commit lifecycle with its retry logic and authentication challenges, and the on-chain metadata system that makes your application discoverable to every node in the network.

If you have followed Articles 1 through 5, you already know how to extend CWindow, register event listeners on CVMContext, manipulate the DFS through CFileSystem, and handle consensus tasks. What you have not yet done is ship. This article bridges that gap.

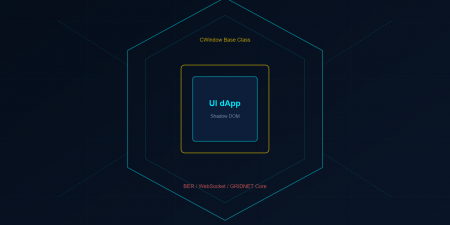

The dApp Architecture — From Window to Blockchain

Before we package anything, let us crystallise what a GRIDNET OS dApp actually is at the architectural level. Every UI dApp in the system follows a consistent pattern, visible across FileManager.js, Terminal.js, and every application in the dApps/ directory.

A dApp is a JavaScript ES module that exports a class extending CWindow. Every dApp class must implement two static methods that serve as its identity:

static getPackageID() {

return "org.gridnetproject.UIdApps.fileManager";

}

static getIcon() {

// Returns the path to the app's icon

}

The getPackageID() method returns a reverse-domain-notation string that uniquely identifies the application throughout the entire GRIDNET OS ecosystem. This is not merely a label — it is the key by which the CPackageManager registers, discovers, and instantiates your application. The Terminal dApp uses "org.gridnetproject.UIdApps.terminal"; the File Manager uses "org.gridnetproject.UIdApps.fileManager". Your third-party dApp should follow the same convention with your own domain.

Inside the constructor, every dApp calls super() with its window geometry, HTML body string, title, icon, and configuration flags. It then registers for the VM events it needs:

constructor(positionX, positionY, width, height) {

super(positionX, positionY, width, height, bodyHTML, "My App", MyApp.getIcon(), false);

// Register for decentralized VM events

CVMContext.getInstance().addVMMetaDataListener(

this.newVMMetaDataCallback.bind(this), this.mID);

CVMContext.getInstance().addNewDFSMsgListener(

this.newDFSMsgCallback.bind(this), this.mID);

CVMContext.getInstance().addVMStateChangedListener(

this.VMStateChangedCallback.bind(this), this.mID);

}

The second argument to each add*Listener() call is the window’s mID — the application ID. This is critical: when your dApp closes, CVMContext.unregisterEventListenersByAppID(appID) iterates through every notification queue in mNotificationListeners and removes all callbacks associated with that ID, preventing memory leaks and phantom event handling.

The Development Workflow — Sandbox Testing and Local Iteration

The development workflow in GRIDNET OS is deceptively simple on the surface but architecturally profound beneath. Your dApp runs inside a browser connected to a full node via WebSocket. The CVMContext singleton manages that connection, tracking its state through a finite state machine: disconnected → connecting → connected.

During development, your iteration loop looks like this:

- Edit your dApp’s JavaScript module — the class extending

CWindow, its HTML body template, its event handlers. - Load it through the Package Manager — the

CPackageManager(instantiated asthis.mPackageManagerin theCVMContextconstructor) discovers and registers available applications duringinitialize(). - Test against the live DFS — your dApp communicates with the decentralised file system through

CFileSystemmethods likedoCD(),doLS(),doSync(). Each returns a request object whosegetReqIDyou track viawindow.addNetworkRequestID(). - Execute GridScript commands — use

CVMContext.getInstance().processGridScript(cmd, threadID, processHandle, mode, reqID)wherethreadIDdefaults tonew ArrayBuffer(),modedefaults toeVMMetaCodeExecutionMode.RAW, andreqIDdefaults to0. For Promise-based dispatch with timeout support, useprocessGridScriptA(). - Observe results — your registered listeners fire when the full node responds.

newVMMetaDataCallbackhandles VM metadata;newDFSMsgCallbackhandles file system responses;newGridScriptResultCallbackhandles GridScript execution results.

The Terminal dApp (Terminal.js) is your primary debugging tool during development. It provides a direct xterm.js-based interface to the GridScript interpreter running on the full node. Through it, you can execute raw GridScript, inspect the DFS, check thread states, and verify that your dApp’s operations produce the expected on-chain effects.

A critical detail for sandbox testing: the CVMContext tracks a mCommitLockTime of 60 seconds — the duration for which a pre-lock on the commit operandi is held before the actual lock is acquired. During development, if a commit gets stuck, call syncVMKF(true, processHandle) to break the lock, send an abort transaction ("at") to the full node, and re-synchronise:

// Break a stuck commit and resynchronize CVMContext.getInstance().syncVMKF(true, myProcessHandle, true);

The third argument (scopeSystemThreadP) ensures the system thread’s scope is reset after the break — essential for preventing scope pollution between test runs.

The GridScript Compilation Pipeline

When your dApp is ready to deploy, its GridScript logic must be compiled into bytecode that the GRIDNET Core virtual machine can execute deterministically across every node in the network. This compilation is performed by GridScriptCompiler.js — a JavaScript implementation that produces bytecode binary-compatible with the C++ GridScriptCompiler in GRIDNET Core’s scriptengine.cpp.

The Codeword Table

At the heart of the compiler lies the codeword table — an ordered array of every operation the GridScript VM understands. The table’s order is sacred: it must exactly match the C++ codeWords[] array in scriptengine.cpp, because opcode IDs are assigned sequentially by position. The base opcode ID is 9 (IDs 0–5 are reserved for special bytecode types: unsigned literals, signed literals, doubles, user opcodes, and string literals; IDs 6–8 are immediate words).

Each codeword definition carries five properties:

// [name, allowedInKernelMode, inlineParams, hasBase58, hasBase64] ['data64', true, 1, false, true], // opcode 9 ['adata64', true, 1, false, true], // opcode 10 ['data', true, 1, false, false], // opcode 11 ['assert', true, 0, false, false], // opcode 12 // ... hundreds more in exact C++ order

The distinction between kernel-mode and non-kernel codewords is paramount for deployment. Only codewords marked allowedInKernelMode = true can appear in on-chain transactions. Operations like keygen (opcode 110), shutdown (opcode 130), or commit (opcode 166) are explicitly non-kernel — they cannot be compiled into deployable bytecode. The compiler enforces this: only kernel-mode codewords are added to the compilation map, and lookups are case-insensitive (matching the C++ implementation).

Opcode Encoding

The encoding scheme is compact and deterministic. For opcode IDs ≤ 127, a single byte suffices. For IDs > 127 (which includes many important codewords like echo at 157, send at 195, or setMeta at 257), the compiler uses a two-byte extended encoding:

setIDBits(id) {

if (id > 127) {

this.mCompilingExtendedID = true;

this.mCurrentOpCode = new Array(2).fill(0);

// High byte with bit 7 set, low byte plain

this.mCurrentOpCode[0] = (id >> 8) | 0x80;

this.mCurrentOpCode[1] = id & 0xFF;

} else {

this.mCompilingExtendedID = false;

this.mCurrentOpCode = [id & 0xFF];

}

}

Content (inline parameters) follows a similar pattern. Lengths ≤ 127 encode in a single byte. Longer content uses an extended encoding where the first byte carries the number of length bytes with bit 7 set, followed by the actual length in little-endian order:

setContentBits(content) {

const length = content.length;

if (length <= 127) {

this.mCurrentOpCode.push(length);

} else {

const numLengthBytes = this.getSignificantBytes(length);

this.mCurrentOpCode.push(numLengthBytes | 0x80);

for (let i = 0; i < numLengthBytes; i++) {

this.mCurrentOpCode.push((length >> (i * 8)) & 0xFF);

}

}

this.mCurrentOpCode.push(...content);

}

The V2 Keyword Hash Chain

Version 2 bytecode introduces a cryptographic integrity mechanism: the keyword image hash chain. Before compilation begins, the compiler initialises a hash seed:

H₀ = SHA-256("GRIDSCRIPT_V2_KEYWORD_IMAGE")

As each codeword is compiled, the hash chain evolves:

Hₙ = SHA-256(Hₙ₋₁ ∥ keyword_name)

The keyword_name preserves the original case from the codeword table (e.g., "regPool" not "regpool"), matching the C++ implementation where activeDefinition->name retains its declared casing. The final hash is embedded in the V2 bytecode header:

V2 Bytecode: [VERSION_BYTE][32-BYTE HASH][OPCODE STREAM]

The version byte is computed as 192 + (version % 64), yielding 194 for V2. Upon decompilation or execution, the receiving node reconstructs the hash chain from the opcodes it encounters and compares it against the embedded hash. A mismatch means the bytecode was compiled with a different keyword set — a tamper detection mechanism that ensures bytecode integrity across the entire network.

V2 Enhancements: Empty Inline Arguments and Flag Support

V2 bytecode introduces two significant enhancements over V1. First, codewords with inline parameters can now be compiled with missing or empty arguments — the compiler stores a zero-length content field, and the decompiler outputs an empty string. V1 bytecode would fail on missing inline arguments; V2 handles them gracefully.

Second, V2 adds flag support for inline parameters. Tokens matching the pattern -flag or +flag (e.g., -t) are recognised as flag prefixes. The compiler consumes both the flag and its following value token, prepending the flag text to the binary parameter data. Multiple flag-value pairs can be collected into a single inline parameter, matching the C++ runtime’s parsing behaviour.

Compiling Your dApp

To compile GridScript source code:

import { GridScriptCompiler } from '/lib/GridScriptCompiler.js';

const compiler = new GridScriptCompiler();

const result = await compiler.compile('echo "Hello, GRIDNET!" cr');

if (result.success) {

// result.bytecode is a Uint8Array of V2 bytecode

const base64 = await GridScriptCompiler.base64CheckEncode(result.bytecode);

console.log('Compiled bytecode (base64Check):', base64);

} else {

console.error('Compilation errors:', result.errors);

}

The compile() method is asynchronous because V2 hash chain computation requires SHA-256 operations, which use the Web Crypto API in browsers and the crypto module in Node.js — the compiler is fully environment-agnostic.

Committing to DFS — The Commit Lifecycle

Compilation produces bytecode. But bytecode alone is inert — a blueprint without a building site. To make your dApp real, you must commit it to the Decentralised File System. This is where GRIDNET OS’s architecture diverges most dramatically from conventional deployment: there is no server to scp files to, no container to push, no CDN to invalidate. Instead, you are writing directly into a consensus-validated, cryptographically authenticated, globally replicated state machine.

The Commit Lock

The commit process begins with a lock. Only one application may commit at a time — the CVMContext enforces this through tryLockCommit(appHandle). The lock is held for mCommitLockTime seconds (default: 60) and is identified by the requesting process’s ID:

// Inside CVMContext.commit()

if (!this.tryLockCommit(appHandle, breakLock)) {

return false; // Lock held by another process

}

if (appHandle.getProcessID !== this.mCommitLockTakenBy) {

return false; // Lock taken by someone else

}

Thread Code Aggregation

When a commit is initiated, the full node aggregates code from all committable threads. The C++ method getCodeFromAllThreads() in scriptengine.cpp iterates through the system thread and all its child threads, collecting their pending code lines. Each thread carries VM flags that determine its behaviour:

isThread— distinguishes sub-threads from the system threadisPrivateThread— marks threads whose code should not be publicly visibleisNonCommittable— excludes threads from the commit aggregationisDataThread— marks data-only threadsisUIAttached— indicates whether a UI is attached to the thread

The aggregated code includes an ERG (Energy Resource Gas) estimation for each thread, computed as getERGUsed() + getFinalTransactionOverheadEstimation() + 1. This estimate determines the computational cost of the transaction on the network.

The DFS Commit Dispatch

The actual commit is dispatched through gFileSystem.doCommit(breakLock, threadID). This sends a DFS datagram to the full node, which then orchestrates the multi-step commit process:

- Receive commit request — the full node acknowledges the DFS datagram

- Aggregate thread code — all committable threads’ code is collected

- Request authentication — the node sends a QR intent or keychain challenge back to the web UI

- Sign the transaction — the user authenticates via QR code scan (mobile app) or local keychain decryption

- Build and broadcast — the signed transaction is broadcast to the network for consensus

Authentication: QR Code vs. Local Keychain

The authentication step deserves special attention. When the full node sends an authentication request (eDataRequestType.QRIntentAuth), the CVMContext‘s processVMMetaDataRequest() method first attempts local keychain signing through the CKeyChainManager:

const handledLocally = await this.mKeyChainManager

.signAuthenticationRequest(targetProcessHandle, request, qr);

if (handledLocally === true) {

// Keychain manager successfully signed AND received confirmation

return true;

} else {

// Fall back to QR code display

this.addGUITask({

id: request.id,

type: eUITTaskType.request,

dataType: request.dataType,

data: qr // QR code object for mobile app scanning

});

}

Local keychain signing is the faster path: the CKeyChainManager unlocks the user’s stored keychain, signs the challenge data, and sends the response directly — no mobile app required. The QR code path is the fallback, displaying a scannable intent that the GRIDNET mobile token app processes.

Commit Monitoring and Retry Logic

After dispatching the commit, the CVMContext enters a monitoring phase through scheduleCommitMonitoring(threadID). This is a sophisticated retry mechanism that handles the inherent unreliability of network communication:

// Retry configuration const commitCheckInterval = 3000; // Check after 3 seconds const maxRetries = 3; const retryDelays = [5000, 10000, 15000]; // Gradual backoff

If the commitPending signal is not received within 3 seconds, the monitor retries the commit with breakCommit=true, allowing the DFS datagram to be resent. After three failed retries (with 5s, 10s, 15s backoff), the system:

- Sends an abort notification to the full node (stopping any pending

askInt()/askString()/askBytes()waits) - Breaks the commit lock to allow recovery

- Sets the Magic Button to error state, notifying the user

The commit state machine tracks progress through eCommitState: none → prePending → pending → success (or aborted). Notably, success and aborted are transient states — they trigger notifications but immediately transition back to none.

Connection Loss During Commit

If the WebSocket connection drops during a commit (the onClose handler fires), the system performs emergency cleanup:

onClose(evt) {

if (this.mCommitLockTaken || this.getIsCommiting) {

this.sendCommitAbortNotification();

this.breakCommitLock();

}

this.setConnectionState = eConnectionState.disconnected;

}

This ensures that a dropped connection never leaves the system in a permanently locked state — a critical safety mechanism for production deployments.

On-Chain Publishing — Making Your App Discoverable

Once your commit succeeds, your dApp exists on-chain. But existence is not the same as discoverability. To make your application findable by other users and by the system’s Package Manager, you need to work with the DFS metadata system.

The GridScript setMeta codeword (opcode 257) writes metadata to DFS entries. Its counterpart getMeta (opcode 259) reads them. Both accept Base58-encoded parameters when the hasBase58 flag is set, allowing you to reference addresses and identifiers in human-readable form.

The DFS supports access control through setfacl (opcode 223) and ownership through chown (opcode 225) — both kernel-mode codewords that can appear in on-chain transactions. You can set permissions on your application’s directory to control who can modify it while keeping it readable by all.

For app registration, the regPool codeword (opcode 301) registers a token pool with Base64-encoded parameters. This mechanism extends to application registration: your dApp’s metadata includes its package ID, version, icon path, and entry point — everything the Package Manager needs to instantiate it.

Versioning and Updates

Updating a deployed dApp follows the same commit pipeline, but with an important consideration: the DFS is append-only at the consensus level. Each commit creates a new data block containing your updated code. The update codeword (opcode 256), update1 (opcode 268), and update2 (opcode 269) provide mechanisms for signalling state transitions within the VM.

The flag codeword (opcode 260) and its dynamic variant flagEx (opcode 261) allow you to set flags on DFS entries, which can be used to mark versions, deprecate old releases, or signal feature availability.

For practical versioning:

- Maintain a version directory structure in DFS (e.g.,

/apps/myapp/v1/,/apps/myapp/v2/) - Update metadata to point the “current” reference to the latest version

- Use

touch(opcode 262) to update timestamps on version directories - Set access controls with

setfaclto prevent unauthorised modifications

Complete Deployment Walkthrough

Let us walk through the entire deployment process for a hypothetical dApp, MyWidget, from development to production.

Step 1: Create Your dApp Module

"use strict"

import { CWindow } from "/lib/window.js"

const widgetBody = `

<style>

.widget-container { padding: 1em; color: #22fafc; }

.widget-btn { background: #1a2744; border: 1px solid #00f0ff;

color: #00f0ff; padding: 0.5em 1em; cursor: pointer; }

</style>

<div class="widget-container">

<h3>My Widget</h3>

<button class="widget-btn commitBtn">Deploy</button>

<div id="statusArea"></div>

</div>

`;

class CMyWidget extends CWindow {

static getPackageID() {

return "com.example.UIdApps.myWidget";

}

static getIcon() {

return "/images/widget-icon.png";

}

constructor(positionX, positionY, width, height) {

super(positionX, positionY, width, height,

widgetBody, "My Widget", CMyWidget.getIcon(), false);

// Register for VM events

CVMContext.getInstance().addVMStateChangedListener(

this.onVMStateChanged.bind(this), this.mID);

CVMContext.getInstance().addVMCommitStateChangedListener(

this.onCommitStateChanged.bind(this), this.mID);

// Bind UI events after DOM renders

this.whenReady(() => {

this.getElement('.commitBtn').onclick =

() => this.handleDeploy();

});

}

async handleDeploy() {

const ctx = CVMContext.getInstance();

// 1. Lock the commit operandi

if (!ctx.tryLockCommit(this)) {

this.showStatus('Commit lock held by another app');

return;

}

// 2. Execute GridScript to write files to DFS

// processGridScript() sends the command asynchronously —

// results arrive via onGridScriptResult callback.

// For the commit to include these changes, the node

// aggregates all thread operations before finalizing.

const reqID = ctx.processGridScript(

'mkdir /apps/myWidget cd /apps/myWidget ' +

'data "widget-config" write config.json',

new ArrayBuffer(), this

);

// 3. Commit to chain (aggregates pending thread operations)

ctx.commit(this, false, 'system');

}

onCommitStateChanged(state) {

switch(state) {

case eCommitState.pending:

this.showStatus('Commit pending — awaiting consensus...');

break;

case eCommitState.success:

this.showStatus('✓ Successfully deployed on-chain!');

break;

case eCommitState.aborted:

this.showStatus('✗ Commit aborted');

break;

}

}

showStatus(msg) {

this.getElement('#statusArea').innerHTML = msg;

}

}

Step 2: Compile GridScript Components

import { GridScriptCompiler } from '/lib/GridScriptCompiler.js';

const compiler = new GridScriptCompiler();

// Compile your on-chain logic

const result = await compiler.compile(

'cd /apps/myWidget ' +

'data "v1.0.0" write version.txt ' +

'setMeta -t myWidgetApp'

);

if (!result.success) {

console.error('Compilation failed:', result.errors);

// Common errors:

// - "Unknown codeword: xyz" — typo or non-kernel codeword

// - "Missing inline parameter for xyz" — V1 mode, missing arg

// - "Invalid base58 parameter" — malformed address

}

Step 3: Test in the Terminal

Open the Terminal dApp and verify your DFS operations work correctly:

mkdir /apps/myWidget cd /apps/myWidget echo "Hello from MyWidget" ls /apps/myWidget

Step 4: Commit and Authenticate

Trigger the commit from your dApp. The system will present an authentication challenge — either handled automatically by the local keychain or via QR code. Upon successful authentication, the transaction is signed, broadcast to the network, and (after consensus) your dApp’s data is permanently written to the DFS.

Step 5: Verify Deployment

After the commit succeeds (your onCommitStateChanged listener fires with eCommitState.success), synchronise and verify:

// Synchronize to confirm on-chain state CVMContext.getInstance().syncVMKF(false, myProcessHandle); // List the deployed files CVMContext.getInstance().getFileSystem.doLS(threadID);

Troubleshooting — Common Deployment Errors and Fixes

“Unknown codeword” during compilation

The codeword you’re trying to compile either doesn’t exist in the codeword table, is misspelled, or is a non-kernel codeword that cannot appear in on-chain bytecode. Check the codeword definition in GridScriptCompiler.js‘s initializeCodewords() method. Remember that lookups are case-insensitive — "Echo", "echo", and "ECHO" all resolve to opcode 157.

V2 keyword image verification failed

This error during decompilation means the bytecode was compiled with a different keyword set than the one the decompiler expects. This typically indicates a version mismatch between the compiler that produced the bytecode and the one trying to read it. Ensure your GridScriptCompiler.js matches the version deployed on the network. The error message includes the first 16 hex digits of both the computed and extracted hashes to aid debugging.

Commit lock timeout

If your commit appears stuck, the most common cause is a failed authentication step or a dropped connection during the commit flow. The automatic retry mechanism (3 attempts with gradual backoff) should recover most transient failures. If it doesn’t, the system breaks the lock after ~30 seconds and resets. You can also manually break the lock:

CVMContext.getInstance().syncVMKF(true, processHandle);

“Network error” during processGridScript

This means sendNetMsg() failed, typically because the WebSocket is not in the OPEN state. Check CVMContext.getInstance().getConnectionState — it should be eConnectionState.connected. If not, the context’s controller thread will automatically attempt reconnection. The connection uses a closest-node heuristic on first attempt, then random selection for subsequent retries.

ERG exhaustion

Every GridScript instruction consumes ERG (Energy Resource Gas). The C++ engine checks ERG before each instruction via the CHECK_ERG macro. If your transaction’s ERG usage exceeds the limit, it fails with “out of ERG.” This is visible in the commit’s thread code aggregation, where each thread reports its ERG estimate. To fix: simplify your transaction, split it into multiple smaller commits, or increase the ERG bid through the transfer mechanism.

Anonymous process calls rejected

All user-mode CVMContext methods require a valid process handle. Calls to processGridScript(), commit(), or syncVM() without a proper handle (an object with getProcessID and getPackageID) are rejected with “Anonymous calls are not allowed.” Ensure your dApp always passes this (the CWindow instance) as the process handle.

Conclusion — The Permanence of Code

There is a philosophical weight to deploying code onto a blockchain that does not exist in traditional software engineering. When you push to a server, you can always push again. When you deploy a container, you can always replace it. But when you commit to the GRIDNET OS Decentralised File System, you are writing into a structure that is, by design, permanent — replicated across every full node, validated by consensus, authenticated by cryptographic signature.

This permanence is both a discipline and a liberation. It demands that you test thoroughly in the sandbox, that you understand the compilation pipeline down to the byte level, that you respect the commit lifecycle’s authentication and retry mechanisms. But it also liberates you from the anxiety of server failures, the fragility of centralised infrastructure, the capriciousness of platform gatekeepers. Your dApp, once committed, exists as long as the network exists.

You began this series by learning to extend a window. You end it by learning to write that window into the permanent record of a decentralised civilisation. The fire has been contained. The forge is ready. Build something worth keeping.