In the grand arc of computing history, every paradigm shift has been preceded by a quietly revolutionary abstraction. The relational database gave structure to chaos. The hyperlink wove a web from isolated documents. And now, in the era of pervasive surveillance and platform monopoly, the GRIDNET OS Swarms API offers something equally transformative: a complete, privacy-preserving framework for decentralized real-time communication — one that requires no central server, no corporate intermediary, and no surrender of personal data.

This article provides a comprehensive, code-level tour of the Swarms API as implemented in GRIDNET OS, drawing extensively from the production Meeting dApp — a fully functional, decentralized video-conferencing application that rivals centralized alternatives while protecting user sovereignty at every layer of the stack.

1. CVMContext — The Operating System’s Nervous System

Every journey through the Swarms API begins at CVMContext, the singleton that represents the entire GRIDNET OS virtual machine context. Think of it as the kernel of a decentralized operating system — it manages cryptographic primitives, network connections, DNS resolution, the window manager, and critically, the CSwarmsManager instance that governs all peer-to-peer swarm activity.

The Meeting dApp obtains its reference to the Swarms Manager through CVMContext at construction time. Note that CVMContext.getInstance().getSwarmsManager is equivalent to CSwarmsManager.getInstance(vmContext) — both return the same singleton:

let ctx = CVMContext.getInstance(); this.mSwarmManager = CSwarmsManager.getInstance(this.mVMContext);

CVMContext also provides essential event buses that dApps subscribe to for system-wide notifications:

ctx.addConnectionStatusChangedListener( this.connectionStatusChangedCallback.bind(this), this.getID ); ctx.addSessionKeyAvailableListener( this.sessionKeyAvailabilityChangedCallback.bind(this), this.getID ); ctx.getSwarmsManager.addLocalStreamEventListener( this.localStreamEventHandler.bind(this), this.getID );

This event-driven architecture is no accident. In a decentralized system, where peers may join or leave at any moment and network conditions fluctuate unpredictably, callback-based state management is not merely convenient — it is essential. The CVMContext pattern ensures that every dApp is a first-class citizen of the operating system, receiving timely notification of connection status changes, cryptographic key availability, and metadata updates without polling.

2. CSwarmsManager — Orchestrating the Mesh

If CVMContext is the kernel, then CSwarmsManager is the network subsystem. This singleton manages the lifecycle of all swarms, governs hardware resource allocation (cameras, microphones, screen capture), and provides the bridge between the operating system’s media layer and the peer-to-peer transport.

The CSwarmsManager maintains a collection of active CSwarm instances and provides methods for joining, leaving, and discovering swarms:

export class CSwarmsManager {

static getInstance(vmContext) {

if (CSwarmsManager.sInstance == null) {

CSwarmsManager.sInstance = new CSwarmsManager(vmContext);

}

return CSwarmsManager.sInstance;

}

constructor(vmContext) {

this.mVMContext = vmContext;

this.mSwarms = [];

this.mLocalStream = null;

this.mScreenStream = null;

this.mDefaultOutgressCapabilities = eConnCapabilities.data;

}

}

One of the most sophisticated aspects of CSwarmsManager is its hardware resource optimization. In a world where privacy is paramount, the manager tracks which swarms actually require camera and microphone access, and releases hardware resources the moment they are no longer needed:

optimizeRequestedResources() {

let audioRequested = false;

let videoRequested = false;

for (let i = 0; i < this.mSwarms.length; i++) {

if (this.mSwarms[i].getCamInUse) videoRequested = true;

if (this.mSwarms[i].getMicInUse) audioRequested = true;

}

if (audioAvailable && !audioRequested) {

this.stopAudioOnly(this.mLocalStream);

// "Releasing microphone as it is no longer needed.."

}

if (videoAvailable && !videoRequested) {

this.stopVideoOnly(this.mLocalStream);

// "Releasing web-cam as it is no longer needed.."

}

}

This is not merely a performance optimization — it is a privacy guarantee. When no dApp requires the webcam, the LED indicator goes dark. The user’s physical environment remains private not because of a software toggle, but because the hardware resource itself is released back to the browser.

3. CSwarm — The Decentralized Room

A CSwarm is the fundamental unit of decentralized collaboration. It represents a group of peers connected through a WebRTC mesh topology, with each participant maintaining direct peer-to-peer connections to every other participant. Unlike centralized conferencing solutions that route all media through a server, each CSwarm is a fully sovereign network.

Every swarm possesses two identifiers: a public ID (used for signaling and discovery) and a true ID (the cryptographic identity used for authentication). This dual-identity design is fundamental to the privacy model described in the MDPI paper “WebRTC Swarms: Decentralized, Incentivized, and Privacy-Preserving Signaling with Designated Verifier Zero-Knowledge Authentication” (Skowroński, 2025).

export class CSwarm {

constructor(swarmManager, agentID, swarmID, trueID) {

this.mMyID = agentID || gTools.convertToArrayBuffer(

gTools.encodeBase58Check(gTools.getRandomVector(16))

);

this.mID = swarmID || gTools.convertToArrayBuffer(

CVMContext.getInstance().getMainSwarmID

);

this.mTrueID = trueID;

// Virtual devices for privacy-preserving muting

this.mVirtualAudioDevice = new CVirtualAudioDev();

this.mVirtualCamDevice = new CVirtualCamDev(640, 480);

this.mLocalDummyStream = new MediaStream([

this.mVirtualAudioDevice.getTrack,

this.mVirtualCamDevice.getTrack

]);

// Connection pools

this.mPendingConnections = [];

this.mActiveConnections = [];

// Security state

this.mSwarmAuthReq = eSwarmAuthRequirement.open;

this.mPasswordImage = new ArrayBuffer();

}

}

3.1 Virtual Devices — The Privacy Layer

One of the most elegant design decisions in the Swarms API is the use of virtual audio and video devices. When a user mutes their microphone or disables their camera, the system does not simply stop sending data — it replaces the real media track with a synthetic one generated by CVirtualCamDev or CVirtualAudioDev. This ensures that the WebRTC connection remains stable (avoiding renegotiation) while revealing absolutely nothing about the user’s environment.

export class CVirtualCamDev {

constructor(widthP = 640, heightP = 480) {

this.mEnabled = true;

this.mTrack = ({ width = widthP, height = heightP } = {}) => {

let canvas = Object.assign(

document.createElement("canvas"), { width, height }

);

canvas.getContext('2d').fillRect(0, 0, width, height);

let stream = canvas.captureStream(25);

return Object.assign(stream.getVideoTracks()[0], {

enabled: this.mEnabled

});

};

this.mTrack = this.mTrack();

}

}

The virtual camera generates a black canvas at 25 fps — indistinguishable from a network perspective from a real video feed, but revealing nothing. The virtual microphone uses a near-silent oscillator at 440 Hz with a gain of 0.1, maintaining the audio pipeline without leaking ambient sound.

3.2 Swarm Security — Public vs. Private

A swarm can operate in two modes: open (public) or private (requiring zero-knowledge proof authentication). The transition between modes is governed by the /setkey command, which the Meeting dApp exposes through its chat interface:

async processCommand(cmd, connection = null) {

switch (cmdWord) {

case 'setkey':

if (params.length == 0) {

this.clearPSK();

this.authRequirement = eSwarmAuthRequirement.open;

return eSwarmCmdProcessingResult.success;

}

let pass = params[0];

if (this.isPasswordNew(pass)) {

let setKeyRes = await this.setPreSharedKey(pass);

if (setKeyRes) {

this.isDedicatedPSK = true;

this.authRequirement = eSwarmAuthRequirement.PSK_ZK;

this.requestAuthentication(true); // Force re-auth

return eSwarmCmdProcessingResult.success;

}

}

break;

}

}

When a swarm becomes private, all active connections are immediately required to re-authenticate. Until a peer proves knowledge of the pre-shared key through the ZKP protocol, they receive only the dummy media tracks — black video and silent audio. The real media tracks are withheld at the CSwarmConnection level through the security checks embedded in the unmute() and replaceVideoTrack() methods.

4. CSwarmConnection — The Peer-to-Peer Channel

Each CSwarmConnection wraps a native RTCPeerConnection and adds the full spectrum of GRIDNET OS security, state management, and event handling. It is the workhorse of the Swarms API — managing ICE negotiation, track replacement, data channel messaging, keep-alive heartbeats, and the complete zero-knowledge proof authentication state machine.

export class CSwarmConnection {

constructor(swarm, rtcPeerConnection, peerID, capabilities) {

this.mRTCConnection = rtcPeerConnection;

this.mSwarm = swarm;

this.mPeerID = peerID;

this.mAuthenticated = false;

this.mAllowedCapabilities = capabilities;

// ZKP state machine

this.mZKPTimer1ExpMS = 10000; // Phase 1 timer

this.mZKPTimer2ExpMS = 3000; // Phase 2 timer

this.mClockDrift = 2000; // Allowed drift

// Event listener queues

this.mSwarmMessageEventListeners = [];

this.mPeerAuthenticationResultListeners = [];

this.mDataChannelStateChangeEventListeners = [];

// ... and many more

}

}

4.1 Connection Politeness — Deterministic Conflict Resolution

In a fully decentralized mesh, two peers may simultaneously attempt to establish a connection with each other, creating a “glare” condition. The Swarms API resolves this deterministically through the isPolite getter, which computes peer dominance by comparing the SHA-256 hashes of both peer identifiers:

get isPolite() {

let cf = CVMContext.getInstance().getCryptoFactory;

let myID = this.mSwarm.getMyID;

let peerID = this.mPeerID;

let mT = cf.getSHA2_256Vec(gTools.convertToArrayBuffer(myID));

let pT = cf.getSHA2_256Vec(gTools.convertToArrayBuffer(peerID));

if (gTools.arrayBufferToBigInt(pT) >

gTools.arrayBufferToBigInt(mT)) {

return true; // "I'll be polite.."

}

return false; // "I've dominated.."

}

This is a textbook implementation of the “perfect negotiation” pattern recommended by the W3C WebRTC specification, but with a uniquely GRIDNET twist: the dominance relationship is cryptographically determined from the peer identifiers, ensuring that the same peer always yields in any given connection pair — no additional signaling required.

4.2 Data Channel Lifecycle and Message Processing

The data channel is the backbone of non-media communication within a swarm. When the data channel opens, the connection transitions to active state, and — if the swarm is private — the ZKP authentication protocol begins immediately:

onDataChannelOpenEvent(event) {

this.setStatus(eSwarmConnectionState.active);

// Authentication gate

if (this.mSwarm.isPrivate) {

this.requestAuthentication(true);

}

this.setNativeConnectionID = event.target.id;

this.mSwarm.transferConnToActive(this.getID);

this.unmute(); // Attempt to send real media (blocked if private + unauthed)

}

Incoming messages traverse a layered processing pipeline. Raw ArrayBuffer datagrams from the WebRTC data channel are first deserialized into CNetMsg containers, then into CSwarmMsg payloads. The connection’s onSwarmMessage() handler acts as a protocol router:

onSwarmMessage(message) {

switch (message.type) {

case eSwarmMsgType.keepAlive:

this.mLastKeepAliveReceivedMS = gTools.getTime(true);

break;

case eSwarmMsgType.zeroKnowledgeProof:

this.processZKP(message.dataBytes);

break;

case eSwarmMsgType.authenticationRequestVal:

let authData = CSwarmAuthData.instantiate(message.dataBytes);

this.processAuthRequestVal(authData);

break;

case eSwarmMsgType.authenticationRequestCand:

this.processAuthRequestCand(message.dataBytes);

break;

// ... media state notifications (mute/unmute/screen share)

}

}

5. CNetMsg and CSwarmMsg — The Data Encapsulation Stack

All data exchanged within a swarm is wrapped in a two-layer encapsulation scheme. CNetMsg provides the transport envelope (protocol ID, request type, payload), while CSwarmMsg provides the application envelope (message type, source/destination IDs, data, timestamp, and optional cryptographic signature).

Both classes use ASN.1 BER encoding for serialization — a deliberate choice that provides platform-independent binary encoding with built-in length prefixing, schema extensibility, and widespread tooling support:

// CSwarmMsg serialization

getPackedData(includeSig = true) {

let wrapperSeq = new asn1js.Sequence();

wrapperSeq.valueBlock.value.push(

new asn1js.Integer({ value: this.mVersion })

);

let mainDataSeq = new asn1js.Sequence();

mainDataSeq.valueBlock.value.push(

new asn1js.Integer({ value: this.mType })

);

mainDataSeq.valueBlock.value.push(

new asn1js.OctetString({ valueHex: this.mFromID })

);

mainDataSeq.valueBlock.value.push(

new asn1js.OctetString({ valueHex: this.mToID })

);

mainDataSeq.valueBlock.value.push(

new asn1js.OctetString({ valueHex: this.mData })

);

mainDataSeq.valueBlock.value.push(

new asn1js.Integer({ value: this.mTimestamp })

);

if (includeSig) {

mainDataSeq.valueBlock.value.push(

new asn1js.OctetString({ valueHex: this.mSig })

);

}

wrapperSeq.valueBlock.value.push(mainDataSeq);

return wrapperSeq.toBER(false);

}

The signature mechanism uses Ed25519 (64-byte signatures), providing authentication and integrity for every message. The signature covers the concatenation of all message fields except the signature itself, preventing tampering at any layer:

sign(privKey) {

let concat = new CDataConcatenator();

concat.add(this.mFromID);

concat.add(this.mToID);

concat.add(this.mVersion);

concat.add(this.mData);

concat.add(this.mTimestamp);

concat.add(this.mType);

let sig = gCrypto.sign(privKey, concat.getData());

if (sig.byteLength == 64) {

this.mSig = sig;

return true;

}

return false;

}

6. The Meeting dApp — Putting It All Together

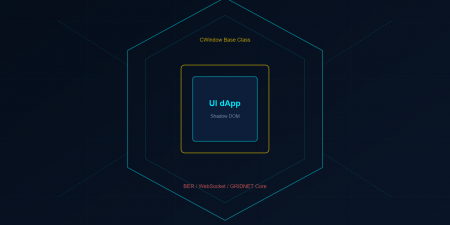

The Meeting dApp (CMeeting) is the flagship demonstration of the Swarms API. Extending CWindow (the GRIDNET OS window manager base class), it implements a complete video-conferencing experience: multi-party video, text chat with typing indicators, screen sharing, emoji reactions, and cryptographic access control — all without a single centralized server in the media path.

class CMeeting extends CWindow {

constructor(positionX, positionY, width, height) {

super(positionX, positionY, width + 200, height,

meetingBody, "⋮⋮⋮ Meeting", CMeeting.getIcon(), true);

this.setProtocolID = 257; // Application-level protocol ID

this.mSwarm = null; // Single swarm per meeting

this.mSwarmManager = CSwarmsManager.getInstance(this.mVMContext);

this.mPeers = [];

this.mMicMuted = true;

this.mCamMuted = true;

this.mSSMuted = true;

this.mMyID = CVMContext.getInstance().getUserID;

}

}

The dApp subscribes to swarm-level events using the appID pattern — a mechanism that ensures clean teardown when the window is closed:

// Subscribing (with appID for cleanup) ctx.addConnectionStatusChangedListener( this.connectionStatusChangedCallback.bind(this), this.getID // appID — used for bulk unsubscription ); // Cleanup on window close ctx.getSwarmsManager.unregisterEventListenersByAppID(this.getID);

This appID-based subscription model is one of the most practical design patterns in the Swarms API. In a multi-window operating system where users may open and close dApps freely, memory leaks from dangling event listeners would be catastrophic. The unregisterEventListenersByAppID() method sweeps through every swarm, every connection, and every event queue, removing all listeners registered by a given application in a single call.

7. Media Management — Camera, Microphone, and Screen Sharing

The Meeting dApp exposes three media toggles: microphone, camera, and screen sharing. Each follows the same pattern: acquire the real media track, set it as the LIVE track on the swarm, then replace the dummy tracks on all active connections:

async toggleCam() {

if (this.mCamMuted) {

// Acquire camera from browser

let stream = await this.mSwarmManager.startCamOnly();

let videoTrack = stream.getVideoTracks()[0];

// Set as LIVE track on swarm

await this.mSwarm.setLIVEVideoTrack(videoTrack, true);

// Notify peers

this.broadcastMediaState(eSwarmMsgType.unmutedCam);

this.mCamMuted = false;

} else {

// Replace with virtual device track

await this.mSwarm.mute(false, true, true, true, 1000);

// Notify peers

this.broadcastMediaState(eSwarmMsgType.mutedCam);

this.mCamMuted = true;

// Release hardware if no other swarm needs it

this.mSwarmManager.optimizeRequestedResources();

}

}

The muting sequence deserves special attention. When the user disables their camera, the system: (1) replaces the live video track with the virtual device’s black canvas, (2) waits approximately 1 second for the replacement to propagate, (3) disables the dummy track’s data flow entirely, and (4) releases the physical camera hardware. This four-step sequence works around known Chromium bugs where simply setting track.enabled = false freezes the last frame rather than showing black.

8. Connection Quality and Keep-Alive

The Swarms API implements a sophisticated connection quality monitoring system. Each CSwarmConnection periodically sends keep-alive datagrams, and the receiving peer measures the time between arrivals to classify connection quality:

// Connection quality thresholds (defined in CSwarm) this.mConnQualityMaxThreshold = 1000; // ms - Excellent this.mConnQualityHighThreshold = 1500; // ms - Good this.mConnQualityMediumThreshold = 2000; // ms - Fair this.mConnQualityLowThreshold = 3500; // ms - Poor this.mPeerReachableTimeoutMS = 5000; // ms - Unreachable

The Meeting dApp renders these quality levels as animated signal-strength icons, providing users with real-time visual feedback about the health of each peer connection — much like the signal bars on a mobile phone, but for peer-to-peer links.

9. Practical Patterns for dApp Developers

For developers building on the Swarms API, the Meeting dApp provides a comprehensive template. Here are the essential patterns:

Pattern 1: Swarm Lifecycle Management

// Join (or create) a swarm — joinSwarm creates internally if needed swarmManager.joinSwarm( trueSwarmID, // Swarm identifier userID, // Your user/agent ID privKey, // Private key for signing eConnCapabilities.audioVideo, // Requested capabilities this // App instance (receives callbacks) ); // Retrieve the swarm reference after join let swarm = swarmManager.findSwarmByID(trueSwarmID); swarm.addClientAppInstance(this); // Register for lifecycle events // Leave on close swarm.removeClientAppInstance(this); // If no clients remain, swarm auto-closes: // "Killing Swarm — all client apps have quit."

Pattern 2: Sending Application Messages

// Send a chat message to all peers

let msg = new CSwarmMsg(

eSwarmMsgType.text,

swarm.getMyID,

new ArrayBuffer(), // broadcast (empty destination)

gTools.convertToArrayBuffer(messageText)

);

msg.sign(this.mPrivKey); // Optional: sign the message

for (let conn of swarm.getActiveConnections) {

conn.sendSwarmMessage(msg, this.setProtocolID);

}

Pattern 3: Handling Authentication Events

// Subscribe for auth results

connection.addPeerAuthResultListener(function(event) {

if (event.result) {

// Peer authenticated — show unlocked icon

this.setPeerAuthStateInUI(event.peerID, 2);

} else {

// Authentication failed — show locked icon

this.setPeerAuthStateInUI(event.peerID, 1);

}

}.bind(this), this.getID);

10. Conclusion — Code as Constitution

The GRIDNET OS Swarms API represents something more than a technical achievement. It is a philosophical statement, encoded in JavaScript: that real-time communication is a fundamental human capability that should not require the permission of any intermediary. Every design decision — from virtual device track replacement to deterministic politeness negotiation to ASN.1-encoded message signatures — serves a single purpose: to make decentralized, privacy-preserving communication not merely possible, but practical.

The Meeting dApp proves this is no theoretical exercise. With its full-featured video conferencing, text chat, screen sharing, and zero-knowledge access control, it stands as a production-grade demonstration that the era of server-dependent communication is drawing to a close. The code speaks for itself — and what it says is that privacy, sovereignty, and real-time collaboration are no longer competing values.

They are, at last, the same thing.

References

[1] Skowroński, R. (2025). “WebRTC Swarms: Decentralized, Incentivized, and Privacy-Preserving Signaling with Designated Verifier Zero-Knowledge Authentication.” Future Internet, 18(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi18010013

[2] W3C. (2024). “WebRTC 1.0: Real-Time Communication Between Browsers.” https://www.w3.org/TR/webrtc/

[3] ITU-T. (2021). “X.690 — ASN.1 encoding rules: BER, CER and DER.” https://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-X.690

[4] GRIDNET OS. (2025). “GRIDNET OS WebUI Source — SwarmManager.js, swarmconnection.js, swarm.js, swarmmsg.js.” https://gridnet.org

[5] Rescorla, E. (2018). “The Transport Layer Security (TLS) Protocol Version 1.3.” RFC 8446. https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc8446

[6] Bernstein, D.J. et al. (2012). “High-speed high-security signatures.” Journal of Cryptographic Engineering, 2(2), 77-89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13389-012-0027-1